One of the challenges of working as a clinician with people in pain is measuring outcomes.

Pain is an experience, and as a result, it cannot be directly measured.

Instead, we use surrogate measures like a VAS, McGill Pain Questionairre and functional assessments to make an assessment of the severity of someone’s complaint.

Often, improving these surrogates become the focus of the treatment, as they are measurable.

From BPS to Enactive

Earlier this year, Peter Stillwell and Katherine Harman wrote an interesting paper titled An enactive approach to pain: beyond the biopsychosocial model, which looked at the issue of compartmentalisation of pain, even with the biopsychosocial model.

They wrote:

With enactivism at the core of this approach, pain does not reside in a mysterious immaterial mind, nor is it an entity to be found in the blood, brain, or other bodily tissues. Instead, pain is a relational and emergent process of sense-making through a lived body that is inseparable from the world that we shape and that shapes us.

When you conceptualise pain this way, it makes it hard to reduce to a questionaire or numerical score, doesn’t it?

Intensity Is Not Proportional To Suffering

One of the big issues with reducing pain down to a score is that it doesn’t capture the human suffering involved.

This is demonstrated in a 2013 paper from Swedish researchers. The authors wrote:

Common symptoms in patients with chronic pain (such as pain intensity, depression, and anxiety) showed great variability across subjects.

That’s not to discount the importance of gauging pain intensity, as the same paper found:

With respect to the investigated aspects of participation and health, pain intensity showed stronger multivariate relationships than psychological symptoms.

Which potentially suggests that for a majority of people, their pain is the primary issue which manifests as psychological symptoms.

However, another paper showed that people with depression experienced nociceptive pain differently (more intensely) compared to healthy controls:

The present study stresses that the initial evaluation of pain intensity among depressed patients is increased compared with HC. This negative bias might affect the way pain is experienced by depressed patients and serve as a mediator between depression and pain complaints.

There is also evidence that factors like controllability can positively influence suffering without changing pain intensity:

control over pain primarily reduces the degree of perceived suffering. This effect was modulated by the subjects’ locus of control: The more participants attributed their behavior to chance, the greater was the reduction of suffering when they had control over their pain. Pain intensity and unpleasantness ratings, by contrast, were unaffected by control over pain.

Though caution must be used when applying this research to practice, as it was experimentally induced pain.

As you can appreciate, even with a small sampling of literature, pain is very “messy”, and difficult to quantify and separate into contributing and effected factors.

Proportion of Patients Making Clinically Significant Improvement

Despite this messiness, something needs to be measured.

Why?

To try and gauge both clinical and economic effectiveness and efficiency of pain management programs and interventions.

Enter the proportion of patients making a clinically significant improvement number.

This is used to gauge how many patients at a particular clinic or hospital improve by at least the minimum clinically significant amount.

Example: the Brief Pain Inventory

A common measure of pain, the Brief Pain Inventory has two aspects – pain intensity looks at worst, best and average pain, where it is felt and the pain interference part looks the impact of this pain on aspects of life.

The minimum clinically significant improvement for this is 10%, and the benchmark for pain clinics is to achieve at least this reduction (in average pain) in at least 30% of patients.

Real World Outcomes Differ To Social Media Outcomes

Given the complex, multi-factorial nature of pain, and the inherent challenges in measuring outcomes, results in real world chronic pain clinics are definitely not eye catching, however they can be life changing.

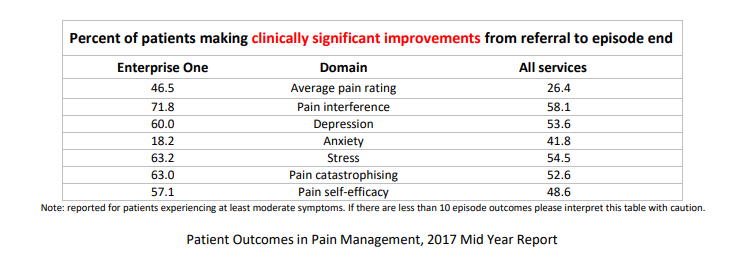

The above image shows outcomes from clinics who participate in the electronic Persistent Pain Outcomes Collaboration (ePPOC). When you look at the “all services” column, it paints a picture of how difficult it is to make clinically significant improvements in each area, with only about a quarter of clinics able to improve average pain rating.

When No Progress Is Progress

Sometimes, we have to accept that the best we can do is stop things from getting much worse.

If you can keep someone’s pain intensity relatively stable, help prevent them catostrophising and falling into depression, then it might not show up as a positive outcome by the numbers, but in reality, it is a HUGE WIN.

Be Optimistic, But Realistic

Instead of delivering false hope for people with advertising and what is said in practice, one of the best things you can do for persistent pain patients is be realistic, in an optimistic way.

That is, explain the facts of their situation, and what is factually known to help and hinder this, but spin it in a way that is positive, and builds confidence in you and potentially themselves that this is the right path for them.

Overall, know that any victories in chronic pain management are hard won, and that it is important for your own health as a practitioner to recognise this and acknowledge your efforts and the role you played in someone’s health. Otherwise, it can be a fast path to burnout.

Author

This post was written by Nick Efthimiou, a contributor to Beyond Mechanical Pain.

References

An enactive approach to pain: beyond the biopsychosocial model

Impact of controllability on pain and suffering

Patient Outcomes in Pain Management – Enterprise One Pain Management Service